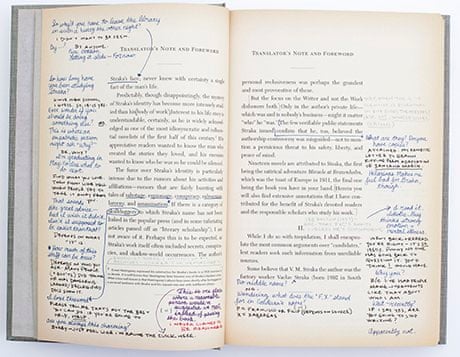

It’s impossible to talk about this book, which, for simplicity’s sake, I will refer to as S, without talking about its production as a physical object, which can only be referred to as “lavish.” A typical page looks like this:

;

;

further, there are objects (postcards, a cypher wheel, loose pages) inserted into the book. So. Let’s talk about it.

There are two books here: first, the fictional V.M. Straka’s Ship of Theseus, which is about a man who is press-ganged onto a strange ship, and second, Doug Dorst and J.J. Abrams’ S, which is about a college student and a grad student who are trying to solve the mystery of who Straka was. The students’ story takes place in the margins: Jen’s handwriting is the cursive in the above page, while Eric’s is the block capitals. Ship of Theseus is not only a book, it’s a code, or so Jen and Eric (and a whole host of other people) believe; it’s complicated by the fact that it’s translated, and that the translator left footnotes, which are their own code, and which are sometimes factually incorrect.

As you can see, it’s complicated.

My feelings about the book, the project itself, and the success of both, are also complicated. J.J. Abrams, as of course many of my readers will know, and I had to google to be sure, directed Lost, which I understand was also about codes and mysteries and sounding complicated. My knowledge of Lost is entirely secondhand, but it’s my impression that many fans felt cheated by the ending (which I don’t have any knowledge of) for not solving anything. They would most likely feel similarly about S: Jen and Eric’s story has an ending which is not unambiguous, but which leaves a lot of ends loose; Ship of Theseus is Symbolic, but I’m not sure what of.

So, what’s the project? Is it to create a Great Book? (That, I think, we can discard immediately.) Or a simple diversion? Or just a labyrinth of misdirection, mirrors, and general confusion? It feels to me as though it’s the third. And does it succeed, on the level of what it was trying to do, and as a book? My answer is a resounding “I’m not sure.”

First of all, I enjoyed it a lot more than I enjoy much metafiction; I thought the extra materials were necessary and not just a gimmick; and the way the marginal text was used (with different colors indicating different times) was actually clever. I kept wondering throughout my reading, though, whether it wouldn’t have been more effective if it had been a traditional narrative, with Ship of Theseus only referenced. The problem with Ship of Theseus being the main text is that the authors have to write something that’s worthy of being analyzed – and to me, much of it seemed like empty symbolism (though that might have been the point). Also, Jen and Eric made jokes based on the the text of the novel, which was fine, except I couldn’t help thinking “but you wrote that too.” It feels circular.

Taking Jen and Eric’s romance as the main story is, I think, the most generous reading. I hope I’m not spoiling anything if I say that they don’t find out who Straka was and that a good 75% of what was mysterious over the book remains mysterious at the end. Jen and Eric, however, who spent most of the book communicating by taking Ship of Theseus out of the library alternately, end up in the same place, having mostly triumphed over the slimy professor and his assistant, who is actually named Ilsa. They’ve grown enough to confess their love for each other, in a very effective way; they’ve experienced interesting character development; they’ve had wins and losses. That aspect is very well executed. And would I have picked it up if it had been a conventional novel about two students trying to solve a literary mystery? Probably not.

But. The literary mystery isn’t solved, and the main text is Ship of Theseus, and isn’t it all maybe a gimmick? And is that a problem? It’s a difficult book to read: you have to physically manipulate it in ways that you don’t with other books; you have to keep parallel texts in mind; you have to keep track of when Jen and Eric are writing. It’s a puzzle. It’s a good puzzle, I have to admit, but I can’t help but feel that it shows a lack of confidence in the material itself.

And let’s just say it: Ship of Theseus isn’t that good. Which is fine, as long as the authors of S know it isn’t. It’s a morass of symbolism, anchored to nothing, except maybe the fictional biography of Straka and his translator. This is, I think, what the point of the story is: “All that ink…is valuable because story is a fragile and ephemeral thing on its own, a thing that is easily effaced or disappeared or destroyed, and it is worth preserving. … We write with what those who’ve come before us wrote.” (450-451, about 5 pages before the end, on a page with very little commentary on it.) And that’s a fragile hook on which to hang your entire project.

So: with all that being said, how do I feel about S? Here’s an answer that’s appropriate: I don’t know. I legitimately cared about Jen and Eric’s story, a story that could have been thin and uninteresting, but which the authors invested in, and thought the ending was very effective. I thought the rest of it was much less effective. I didn’t, in all honesty, expect to have the mysteries solved, but it’s slightly frustrating that they were left so open.

Here is a line that I will draw at the bottom: it’s well-executed, and much better than it could have been, and I enjoyed reading it.

P.S. This blog has, up to now, reviewed books that were unambiguously SFF. Is this SFF? I mean, probably. There’s a ship of the dead at the center of it. But it’s not really the point of the book. It is, however, one of the more interesting things I’ve read lately.